It's what all the cool kids are (still) talking about, so why not a post on it? In the glut of Kepler mission transiting planets, a new planet has risen to the fore as the possibly most Earthlike extrasolar planet. Huzzah! (And in a few months yet another new planet will take its place. Just watch).

What we know

Kepler 22 is a star very similar to our sun. It is slightly smaller (0.98 times the radius of the sun) and slightly smaller (0.97 times the mass of the sun). It is 587.1 light years away, so it's not something we're going to be visiting soon.

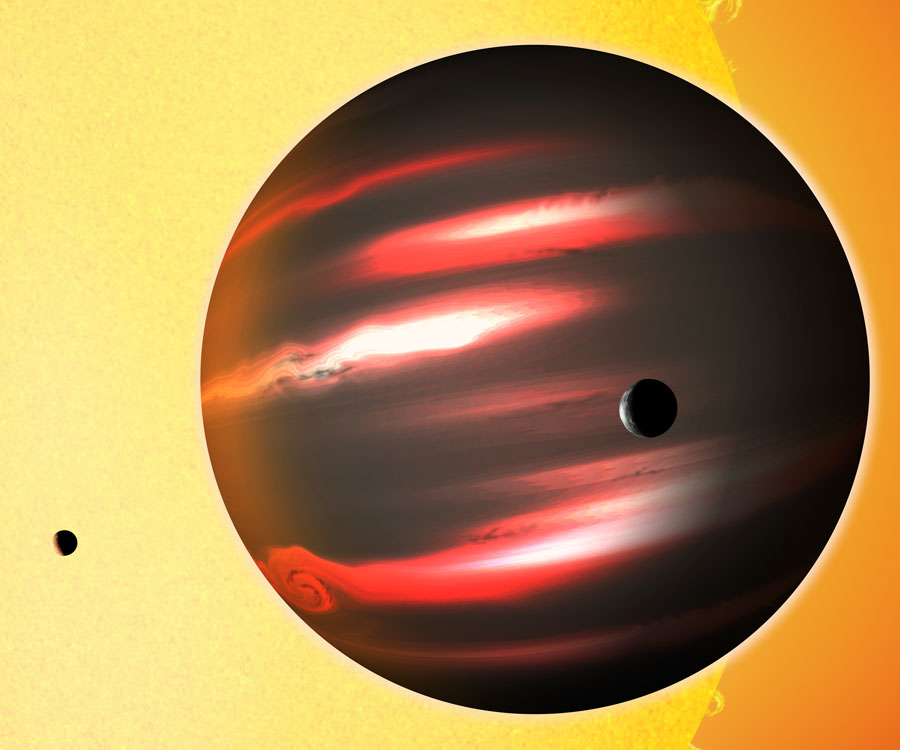

So far, it only has one known planet, dubbed -- as these things go -- Kepler 22b. This planet is smack bang in the habitable zone ...on the inner edge, so OK, maybe not that smack bang... BUT. The part people are getting exciting about is that it's the smallest planet we've found in the habitable zone thus far.

How small? 2.38 Earth radii. For comparison, Neptune, the next biggest solar planet after Earth, is 3.88 times Earth's radius. That puts Kepler 22b just on the smaller side of halfway between Earth and Neptune. In terms of size.

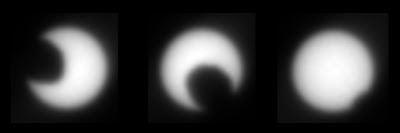

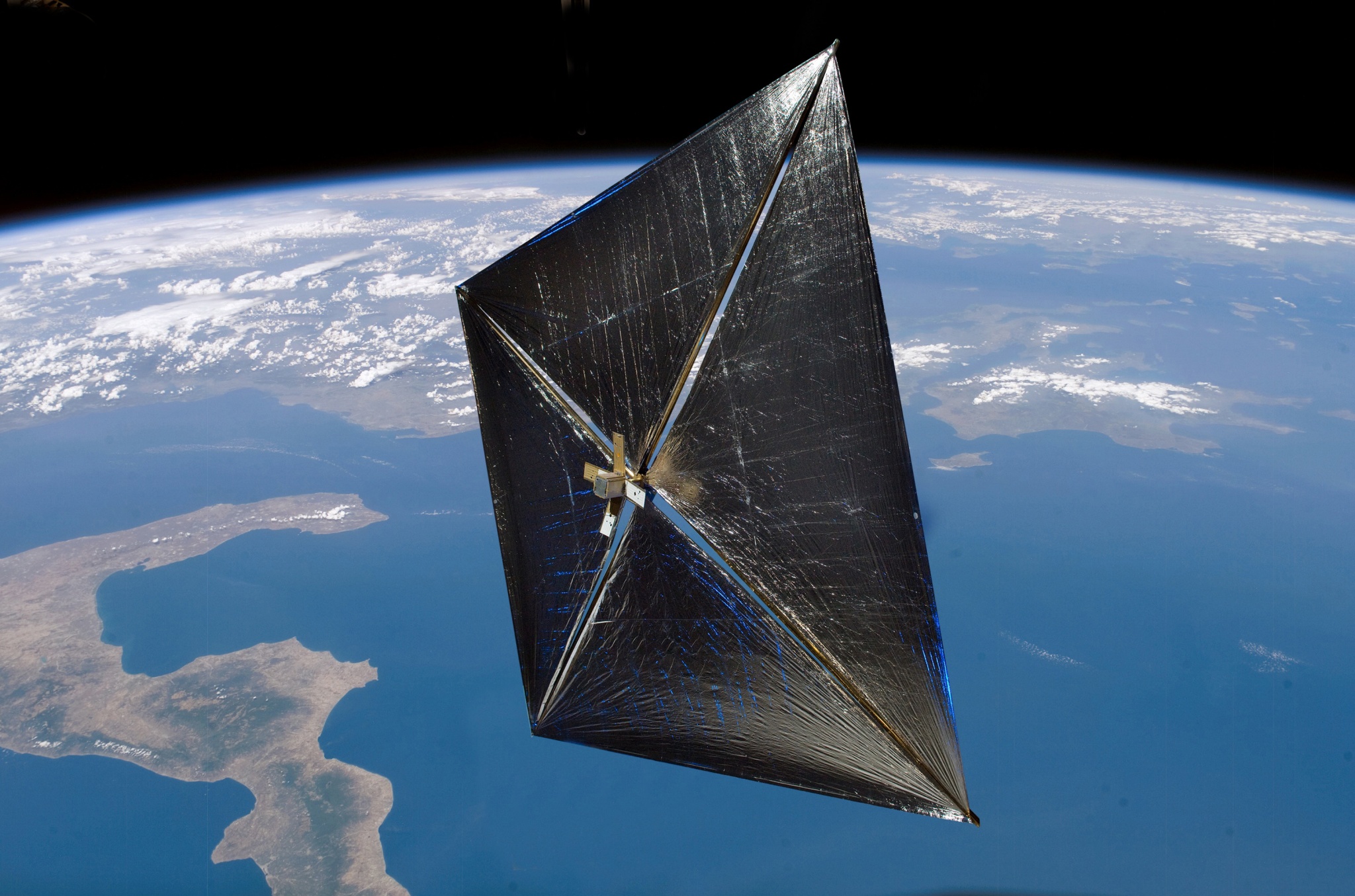

What we don't know is how massive it is. The way the Kepler satellite detects exoplanets is by looking at stars and measuring how much dimmer they get when (if) a planet passes between the star and us. By knowing how much light the star gives out usually, and how far away it is, it's possible to work out how large the planet is. (And, actually, even if you don't know how far away the star is, you could still work out how big the planet has to be as a fraction of the size of the star.)

We know how long its year is, basically by measuring how often it passes in front of the star. Yeah. It's that simple (particularly since there seems to be just one planet in this system at the moment). So Kepler 22b's year is 290 days long, not drastically different to Earth's. That and its position in the habitable zone have lead people to suppose that maybe it's not so different to Earth.

Based on how far it is from its star etc, the average surface temperature would be about -11º Celsius if it had no atmosphere. However, if it had an atmosphere like Earth's average temperature would be about 22º C. Perhaps a slightly less insulating atmosphere would be in order, however, since Earth's mean surface temperature is actually 14º C. (Because we have to take global lows and highs into account, you see, and average over the whole planet, never mind that 22º is just about room temperature.)

Harping on what we don't know

It's that mass. And the fact that we don't have a planet of that size in our solar system. It's in the transitional zone, as I said, between rocky terrestrial planet and mini gas giant. If it's rocky, it's likely that the gravity will be stronger than Earth's, thanks to it's larger size. In fact, if it's the same density as Earth, the surface gravity will be about 2.4 times Earth. Which isn't long-term viable. At Neptune's density, we get a ball of gas with surface gravity 0.72 times Earth. A ball of ice would result in gravity 4.3 times Earth. The least dense terrestrial planet in our solar system is Mars and at Mars' density, Kepler 22b would have gravity 1.7 Earth's.

So there's quite a spectrum of possibilities there. We really don't know enough to make any definitive judgements at this stage. That doesn't make it less exciting, of course, and it's true that there might be oceans and continents there. Or it could be a small dense ball with a thick gaseous atmosphere inhabited by dragons (perhaps even fire-breathing ones, if there's methane in the atmosphere and breathing fire is a viable way to catch prey). Which would also be cool. Arguably, cooler.

|

| Credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech |

What we know

Kepler 22 is a star very similar to our sun. It is slightly smaller (0.98 times the radius of the sun) and slightly smaller (0.97 times the mass of the sun). It is 587.1 light years away, so it's not something we're going to be visiting soon.

So far, it only has one known planet, dubbed -- as these things go -- Kepler 22b. This planet is smack bang in the habitable zone ...on the inner edge, so OK, maybe not that smack bang... BUT. The part people are getting exciting about is that it's the smallest planet we've found in the habitable zone thus far.

How small? 2.38 Earth radii. For comparison, Neptune, the next biggest solar planet after Earth, is 3.88 times Earth's radius. That puts Kepler 22b just on the smaller side of halfway between Earth and Neptune. In terms of size.

What we don't know is how massive it is. The way the Kepler satellite detects exoplanets is by looking at stars and measuring how much dimmer they get when (if) a planet passes between the star and us. By knowing how much light the star gives out usually, and how far away it is, it's possible to work out how large the planet is. (And, actually, even if you don't know how far away the star is, you could still work out how big the planet has to be as a fraction of the size of the star.)

We know how long its year is, basically by measuring how often it passes in front of the star. Yeah. It's that simple (particularly since there seems to be just one planet in this system at the moment). So Kepler 22b's year is 290 days long, not drastically different to Earth's. That and its position in the habitable zone have lead people to suppose that maybe it's not so different to Earth.

Based on how far it is from its star etc, the average surface temperature would be about -11º Celsius if it had no atmosphere. However, if it had an atmosphere like Earth's average temperature would be about 22º C. Perhaps a slightly less insulating atmosphere would be in order, however, since Earth's mean surface temperature is actually 14º C. (Because we have to take global lows and highs into account, you see, and average over the whole planet, never mind that 22º is just about room temperature.)

Harping on what we don't know

It's that mass. And the fact that we don't have a planet of that size in our solar system. It's in the transitional zone, as I said, between rocky terrestrial planet and mini gas giant. If it's rocky, it's likely that the gravity will be stronger than Earth's, thanks to it's larger size. In fact, if it's the same density as Earth, the surface gravity will be about 2.4 times Earth. Which isn't long-term viable. At Neptune's density, we get a ball of gas with surface gravity 0.72 times Earth. A ball of ice would result in gravity 4.3 times Earth. The least dense terrestrial planet in our solar system is Mars and at Mars' density, Kepler 22b would have gravity 1.7 Earth's.

So there's quite a spectrum of possibilities there. We really don't know enough to make any definitive judgements at this stage. That doesn't make it less exciting, of course, and it's true that there might be oceans and continents there. Or it could be a small dense ball with a thick gaseous atmosphere inhabited by dragons (perhaps even fire-breathing ones, if there's methane in the atmosphere and breathing fire is a viable way to catch prey). Which would also be cool. Arguably, cooler.