This blog post is about how supernovae affect civilisations. I've mentioned them before in the context of sterilising planets and hence halting the development of life. Today, I talk about supernovae that are distant enough to not kill everything while still being clearly visible to the unaided eye.

Historically

In the past millennium, there have been several (obviously non-sterilising) supernovae visible from Earth. We know about them thanks to various historical records, which tend to get more scientific as they become more recent. Don't think that being distant enough not to kill us means that they aren't bright. Most of them have been brighter than all the other objects in the night sky (other than the moon) and some were even still visible during the day.

Some comments on the Milky Way's historical supernovae:

- Lupus is now the remnant of a supernova which exploded in 1006. It is 2.2 kpc away (kpc = kiloparsecs; that distance is 7200 light years). It was visible during the day and apparently illuminated the landscape at night. (Interesting fact: if you take out the moon, it was brighter than the rest of the night sky put together.) It was recorded by Chinese, Arabic and European astronomers of the day.

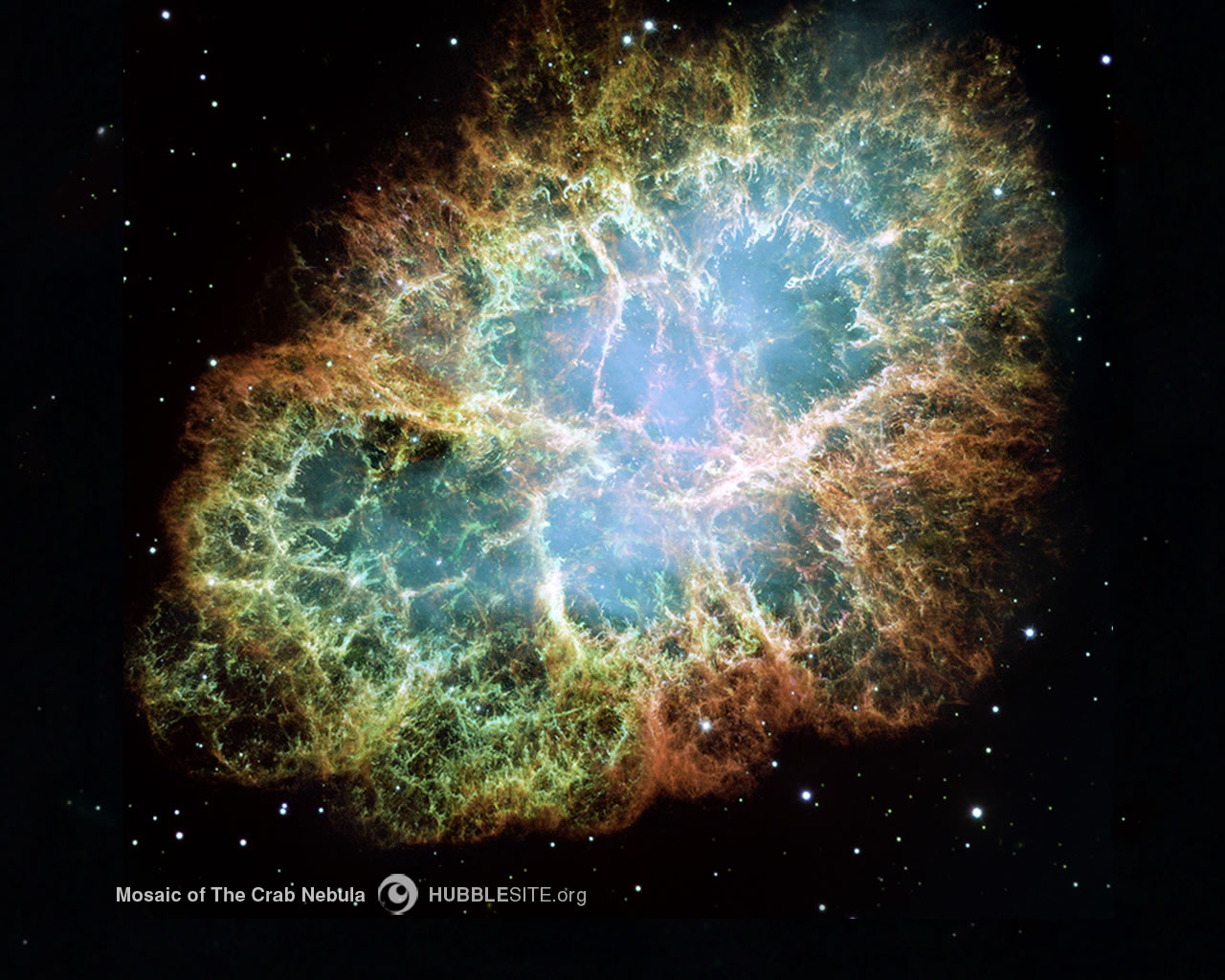

- Crab, as in the Crab Nebula and the Crab pulsar, is the remnant of the supernova that exploded in 1054. It is about 2 kpc (= 6500 light years) away and was well documented throughout Asia and the Middle East. It was visible in the sky for two years, though it was less bright than Lupus (due to there being more dust obscuring its light in that direction), it was very much visible during the day.

Crab Nebula Mosaic from HST

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, J. Hester, A. Loll (ASU)

Acknowledgement: Davide De Martin (Skyfactory) - 3C 58 is one of the less inspiring names for a supernova remnant (pre-dominantly pulsar in this case). It was seen in 1181 by Chinese and Japanese astronomers and was only visible a night albeit as the brightest star in the sky. It's possible that the pulsar in that direction is older than the supernova event, but its hard to know for certain. It is 3.1 kpc (= 10 000 light years) away.

- Tycho is the next supernova on the list. It exploded in 1572 and is named after Tycho Brahe not because he discovered it (how can you "discover" something that everyone can see, even during the day) but because he studied it extensively (some have said obsessively). It inspired him (and others) to revolutionise the astronomy of the day.

- Kepler came next, with his supernova which was first observed in 1604. (4.8 kpc = 15 600 light years away.) It was bright enough to be visible during the day, but not when the sun was high. As with Tycho, Kepler didn't discover it but he wrote a book about it, which led to it being named after him. Wiki says this was the most recent observed supernova in the Milky Way, but there are two more about which less fuss was made because they were less glaringly obvious.

- Cassiopeia A probably exploded in 1680 but that date uncertain. It was noted down in a routine sky catalogue by the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, then later erased as an erroneous entry because there was no long a star at that location. The modern remnant wasn't discovered until 1947, after which it was linked to the erroneous catalogue entry. Although the remnant is 3.4 kpc (= 11 000 light years) away, it wasn't easily visible because of the large amount of dust in that direction.

- Speaking of dust, this last supernova is an interesting case. It doesn't have a nice name, merely one based on its galactic co-ordinates: G1.9+0.3, or G1.9 for short. No one saw it explode. there is a lot of dust in that direction. Most of the dust in the Milky Way lies in the plane of the disc and, looking towards G1.9, we are looking right through that disc of dust. From the speed of the remnant expansion, we predict that it exploded around 1868. Anyway, this one is less relevant to the thrust of this post, I just thought it was cool.

Because I can, here is a little graphic showing the various directions of these supernovae:

|

| Image credit: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss |

Auspicious portent?

So supernovae are pretty cool (or incredibly hot, if you want to be literal about it) and now it's time to tie it back into stories.

Before we, as civilisations, knew what supernovae really were (and to be fair, that occurred relatively recently, compared with all those historical supernovae), they were seen as new stars, visiting stars. In fact that's what the "nova" part indicates: newness.

Lacking a physical explanation, imagine what those people must have thought when a new light appeared in the sky and then, incredibly, was visible during the day. It's the sort of thing that, these days, might make someone less abreast of astronomy think of aliens. What would it have been back then? Portents?

We know that comets were often hailed as portentous, so why not an auspicious supernova? Supernovae are even rarer which, one would think, would make them even more significant, mythologically speaking. In a world of myth and legend, what might the appearance of a bright new star lead people to do? I hesitate to suggest that people would panic (unless goats with two heads were born at the same time, maybe) but it would surely affect their lives. Especially if it lit up the night enough to see by (like Lupus probably did).

In a world of myth and legend, what might someone do if a new star lit up the day sky? Would they, perhaps, set out on a quest to follow it? What would their reaction be to whatever they found beneath it on their journey?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Have a question or comment? Feel free to leave a response, even on old posts.